I didn’t sleep much the week I arrived in Tokyo in December 1998. Not from jet lag, though that certainly didn’t help. No, I was buzzing with nerves and anticipation, preparing to lead the most ambitious balloon project of my life. It was my first trip to Japan, and it was for a New Year’s Day television special on Fuji TV. The assignment? Train a team of Japanese celebrities to create an enormous sculpture entirely out of balloons—with cameras rolling. This is what reality television looked like around the turn of the century.

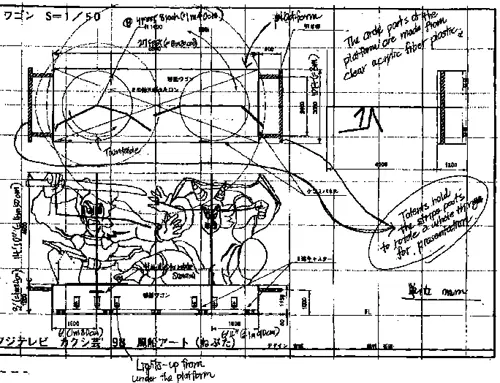

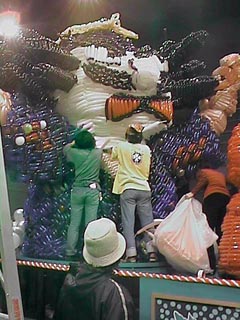

The theme was a nebuta—a traditional Japanese figure, often used in illuminated parade floats. Ours would feature a samurai locked in battle with a demon, the samurai’s sword coming down to sever his enemy’s head. This thing was going to be eight meters wide, four and a half meters tall, and four meters deep. Oh, and it would move. Specifically, the sword-bearing arm would raise and slice, and the body would rotate to face his fierce enemy.

I had designed the whole piece before boarding the plane. I had concerns about building a sculpture this size. I had never constructed a balloon piece this large, and to the best of my knowledge, no one else had either. I was somewhat confident I knew how to make it work, but there was still this nagging concern that an air-filled sculpture would compress under its own weight. Still, that wasn’t what worried me most. After all, I’d solve that problem if I encountered it. That was just engineering. What kept me up at night was the thought of trying to teach balloon twisting to a group of people who didn’t speak my language. I didn’t speak theirs either. Everything would have to happen through a translator and, even without communication challenges, I had no idea how skillfully I could get my untrained crew to work.

Interpretive Dance

My home, Rochester, NY, has one of the largest Deaf communities in the United States. Because of that, I often have American Sign Language (ASL) interpreters on stage with me. My performances tend to be very visual, and I always try to honor my Deaf audience members by considering their experience: I position myself so they can see both me and the interpreter clearly, make sure the interpreter is well-lit, and keep sight lines open. It’s second nature now. Making the interpreter visible is part of making the performance accessible.

Japan was the first time I worked with an interpreter for another spoken language. Almost as soon as I arrived, I met Kiyomi, who would be translating everything I said into Japanese. Within minutes of our introduction, I was in front of a camera for a TV interview.

As I began to speak, I realized Kiyomi was standing behind me, just outside the camera’s frame. Instinctively, I moved aside so the camera could see her while she spoke. It was the same adjustment I always made with ASL interpreters. I make space for the voice the audience hears. But when I noticed the camera following me and putting her back out of sight, I moved again. And again. We began an unintentional dance, with me trying to bring her into view and her trying to stay out of it.

Eventually, Kiyomi gently tapped me on the shoulder and asked why I kept moving.

“I’m just trying to make sure the audience sees you,” I explained.

She said sternly, “But I’m not the one being interviewed. You are. I’m just your Japanese voice. I shouldn’t be seen.”

It hadn’t occurred to me that spoken-language interpreters avoid being on camera. It was the first time in my life I had to hide my own “voice.” That moment stuck with me—a simple but profound lesson in how different types of communication require different forms of visibility.

The crew

Fuji TV gave me eight celebrities—actors, comedians, even a model—and seven full-time crew members who’d assist with the actual building, day and night if needed. The celebrities would appear on camera, learning and helping with the construction, but the real lifting was on the crew.

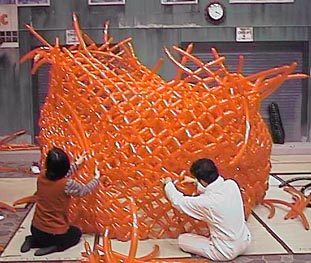

The training sessions were short, only about two hours per celebrity at a time, and the cameras rolled the whole way through. I had to demonstrate something once, then move on, hoping it would stick. Behind the scenes, the crew I worked with was incredibly dedicated. They were patient, eager, and willing to work twelve-hour days without complaint. At first, they followed my directions too precisely—no experimenting, no improvising. But after a couple of long days, something shifted. They began to understand not just the how, but the why behind the twists. They started to understand where supports were needed, how the balloons behaved, and when it was better to replace than fix pieces. That’s when it started to come together.

The celebrities surprised me too. Some were naturally gifted with their hands, some less so. A few were clearly more interested in mugging for the camera than building the sculpture. Entertainers entertain. Obvious enough. But put a bunch of performers in a room to learn a new skill, turn on a camera, and suddenly everyone’s more focused on looking good than learning anything. But most genuinely tried, and it showed. It wasn’t just for the cameras. They wanted to do it.

Sure, I like building massive balloon sculptures—but first and foremost, I’m an entertainer. I wanted to play for the camera just as much as they did. The difference? They were warned when the cameras would be rolling. Some even knew when to reapply their makeup. I, on the other hand, never had a clue when a camera would pop up. No script. No cues. No idea what room I might get filmed in. For nine days in a country I’d never been to, surrounded by people speaking a language I didn’t understand, I could’ve really used a cheat sheet. Still, it was fun. I smiled for the camera. I joked around. There was always a delay before I got a reaction—everything had to be translated—but eventually, laughter would come, and that felt like gold.

I did my best to keep the atmosphere light, relying heavily on humor and facial expressions. Not knowing the language was frustrating. I’d say something that I thought was clever, hand it off to Kiyomi, and then wait. If the room erupted in laughter, I’d assume she passed it along faithfully. If it didn’t land, well, maybe my clever American thought simply couldn’t be translated. I’ll never really know for sure. But we laughed a lot, and that was enough.

Construction

In the end, the sculpture used about 15,000 twisting balloons—most of them the classic 260s—also known as “pencil balloons”, these are the ones you usually see being used to make small figures in restaurants and birthday parties. My role shifted constantly. I was the designer, the teacher, the project manager, and, more than anything, the one who stayed awake worrying when everyone else took breaks. The final build was a 36-hour marathon. I managed to sleep for two of those hours. Just enough time for the crew to attach a part of the sculpture without me, creating a problem that later took two hours to fix. A ten-minute job, if I’d been awake. But I couldn’t be mad. They were trying to help.

We kept the internal frame as minimal as possible. Since the whole thing had to move outdoors, we added a simple T-shaped support inside the samurai and the demon, mostly for insurance. But structurally, the sculpture stood on its own. Most of it was built off the frame and later assembled like a massive, inflatable puzzle.

The samurai’s face nearly derailed us. Not because it was hard to build—though it was—but because we hit a wall of cultural misunderstanding. I had done my research before flying out, poring over photos and illustrations of samurai. My version leaned into the dramatic, armored warrior with intense expressions. But the production team wanted something softer, more symbolic. A patterned kimono. A calmer look. It took some back and forth, and more than a few redrawn sketches, but we got there. The final design used a kabuki-style white face, and we spent hours adjusting the expression until it felt just fierce enough.

The head, which was built early in our work sessions, was the last thing we attached. I had hoped to place it sooner, just for peace of mind, but the director wanted to end with a flourish. It made for good television, sure, but also for an anxious crew and one very stressed art director.

The demon offered a whole different set of challenges. It had to contrast sharply with the samurai, so we pushed the proportions into something more monstrous. The face alone stood twelve feet tall. We constructed the head in three sections: a wide central cylinder, a dish-shaped top, and a lower portion that we installed last. Unfortunately, the top went on while I was napping—my one real break. That made finishing the lower section a logistical nightmare. The demon’s head hung three feet above the platform while we scrambled to build upward beneath it.

The hair, which I had originally designed to be full and rigid like the samurai’s, had to be simplified. We ran out of time. Instead, we jammed fully inflated balloons into the scalp area, creating a wild, chaotic look that actually worked better than expected.

As for the facial features (eyes, fangs, and so on), we built them separately and attached them once the structure was up. It took tall ladders and a lot of hands to get everything in place. Thinking back, I wonder if our ladder usage would have met OSHA requirements.

Throughout the project, the biggest creative challenge wasn’t balloons. It was communication. I’m not much of a traditional illustrator. My sketches have gotten better over the years, but even today, most of the final sketches we show to crew are made by Kelly. Balloons are my pencils. For this job, though, years before I met Kelly, I had to produce diagrams in advance. They wanted to know what I planned to build before I arrived, which was fair. But translating a mental image of a sculpture into a two-dimensional drawing, and then into a cross-cultural collaboration, required more patience than I had packed.

We made it work. When it was done, the sculpture stood proud. The samurai and the demon, locked in eternal combat, surrounded by lights, cameras, and a room full of exhausted, smiling humans. It didn’t matter that we spoke different languages or came from different places. We built something together, with balloons, with laughter, and with very little sleep.

I still think about that project every time I take on something big. It was the first time I led a team through something truly massive. The first time I handed off my designs to others and trusted them to bring it to life. And the first time I realized just how universal art can be—even when made from something as ridiculous and wonderful as balloons. My career focus on community-built art was launched.

Very fun story to read. So many interesting details that made me feel like I experienced it with you.

P.S. I’ll never drink Coca-Cola again lol

I think I stopped for a while, but it didn’t keep me away from Coke for too long. It’s still something I know how to order in other countries that they’re almost certain to have. And in some countries, the only way I’ve found to order soda is to ask for Coca-Cola. Then they ask what kind, as it’s a generic term for all soda.